The Python logging package is a a lightweight but extensible package for keeping better track of what your own code does. Using it gives you much more flexibility than just littering your code with superfluous print() calls.

However, Python’s logging package can be complicated in certain spots. Handlers, loggers, levels, namespaces, filters: it’s not easy to keep track of all of these pieces and how they interact.

One way to tie up the loose ends in your understanding of logging is to peek under the hood to its CPython source code. The Python code behind logging is concise and modular, and reading through it can help you get that aha moment.

This article is meant to complement the logging HOWTO document as well as Logging in Python, which is a walkthrough on how to use the package.

By the end of this article, you’ll be familiar with the following:

logginglevels and how they work- Thread-safety versus process-safety in

logging - The design of

loggingfrom an OOP perspective - Logging in libraries vs applications

- Best practices and design patterns for using

logging

For the most part, we’ll go line-by-line down the core module in Python’s logging package in order to build a picture of how it’s laid out.

Free Bonus: 5 Thoughts On Python Mastery, a free course for Python developers that shows you the roadmap and the mindset you'll need to take your Python skills to the next level.

How to Follow Along

Because the logging source code is central to this article, you can assume that any code block or link is based on a specific commit in the Python 3.7 CPython repository, namely commit d730719. You can find the logging package itself in the Lib/ directory within the CPython source.

Within the logging package, most of the heavy lifting occurs within logging/__init__.py, which is the file you’ll spend the most time on here:

cpython/

│

├── Lib/

│ ├── logging/

│ │ ├── __init__.py

│ │ ├── config.py

│ │ └── handlers.py

│ ├── ...

├── Modules/

├── Include/

...

... [truncated]

With that, let’s jump in.

Preliminaries

Before we get to the heavyweight classes, the top hundred lines or so of __init__.py introduce a few subtle but important concepts.

Preliminary #1: A Level Is Just an int!

Objects like logging.INFO or logging.DEBUG can seem a bit opaque. What are these variables internally, and how are they defined?

In fact, the uppercase constants from Python’s logging are just integers, forming an enum-like collection of numerical levels:

CRITICAL = 50

FATAL = CRITICAL

ERROR = 40

WARNING = 30

WARN = WARNING

INFO = 20

DEBUG = 10

NOTSET = 0

Why not just use the strings "INFO" or "DEBUG"? Levels are int constants to allow for the simple, unambiguous comparison of one level with another. They are given names as well to lend them semantic meaning. Saying that a message has a severity of 50 may not be immediately clear, but saying that it has a level of CRITICAL lets you know that you’ve got a flashing red light somewhere in your program.

Now, technically, you can pass just the str form of a level in some places, such as logger.setLevel("DEBUG"). Internally, this will call _checkLevel(), which ultimately does a dict lookup for the corresponding int:

_nameToLevel = {

'CRITICAL': CRITICAL,

'FATAL': FATAL,

'ERROR': ERROR,

'WARN': WARNING,

'WARNING': WARNING,

'INFO': INFO,

'DEBUG': DEBUG,

'NOTSET': NOTSET,

}

def _checkLevel(level):

if isinstance(level, int):

rv = level

elif str(level) == level:

if level not in _nameToLevel:

raise ValueError("Unknown level: %r" % level)

rv = _nameToLevel[level]

else:

raise TypeError("Level not an integer or a valid string: %r" % level)

return rv

Which should you prefer? I’m not too opinionated on this, but it’s notable that the logging docs consistently use the form logging.DEBUG rather than "DEBUG" or 10. Also, passing the str form isn’t an option in Python 2, and some logging methods such as logger.isEnabledFor() will accept only an int, not its str cousin.

Preliminary #2: Logging Is Thread-Safe, but Not Process-Safe

A few lines down, you’ll find the following short code block, which is sneakily critical to the whole package:

import threading

_lock = threading.RLock()

def _acquireLock():

if _lock:

_lock.acquire()

def _releaseLock():

if _lock:

_lock.release()

The _lock object is a reentrant lock that sits in the global namespace of the logging/__init__.py module. It makes pretty much every object and operation in the entire logging package thread-safe, enabling threads to do read and write operations without the threat of a race condition. You can see in the module source code that _acquireLock() and _releaseLock() are ubiquitous to the module and its classes.

There’s something not accounted for here, though: what about process safety? The short answer is that the logging module is not process safe. This isn’t inherently a fault of logging—generally, two processes can’t write to same file without a lot of proactive effort on behalf of the programmer first.

This means that you’ll want to be careful before using classes such as a logging.FileHandler with multiprocessing involved. If two processes want to read from and write to the same underlying file concurrently, then you can run into a nasty bug halfway through a long-running routine.

If you want to get around this limitation, there’s a thorough recipe in the official Logging Cookbook. Because this entails a decent amount of setup, one alternative is to have each process log to a separate file based on its process ID, which you can grab with os.getpid().

Package Architecture: Logging’s MRO

Now that we’ve covered some preliminary setup code, let’s take a high-level look at how logging is laid out. The logging package uses a healthy dose of OOP and inheritance. Here’s a partial look at the method resolution order (MRO) for some of the most important classes in the package:

object

│

├── LogRecord

├── Filterer

│ ├── Logger

│ │ └── RootLogger

│ └── Handler

│ ├── StreamHandler

│ └── NullHandler

├── Filter

└── Manager

The tree diagram above doesn’t cover all of the classes in the module, just those that are most worth highlighting.

Note: You can use the dunder attribute logging.StreamHandler.__mro__ to see the chain of inheritance. A definitive guide to the MRO can be found in the Python 2 docs, though it is applicable to Python 3 as well.

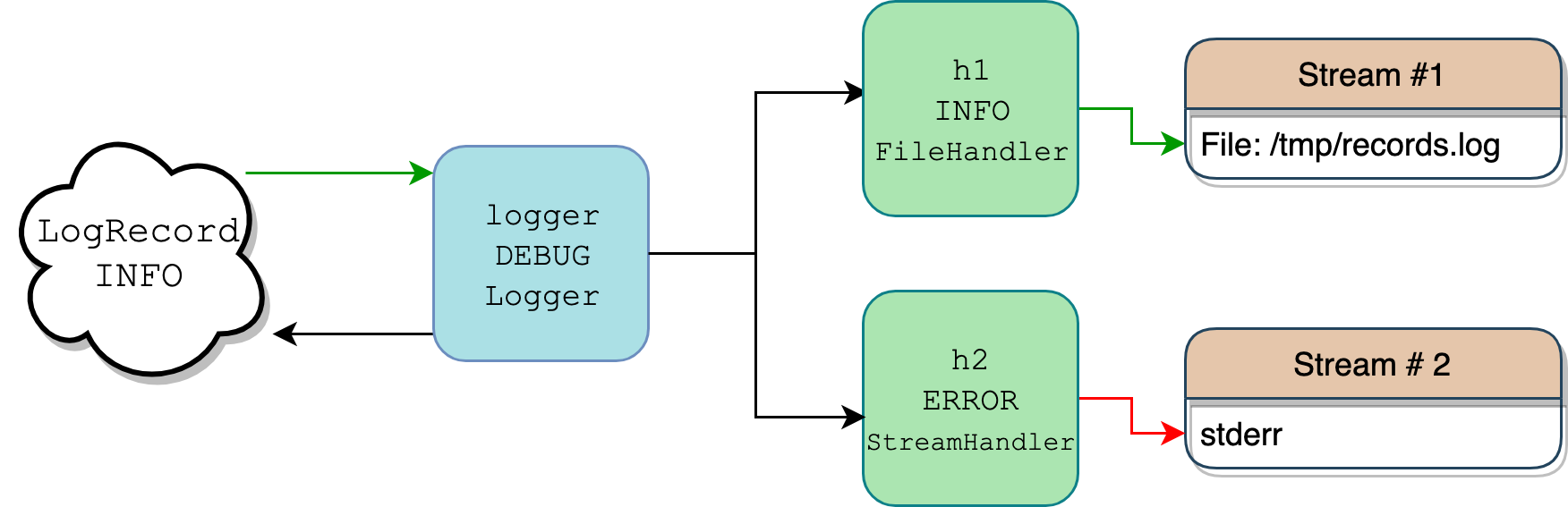

This litany of classes is typically one source of confusion because there’s a lot going on, and it’s all jargon-heavy. Filter versus Filterer? Logger versus Handler? It can be challenging to keep track of everything, much less visualize how it fits together. A picture is worth a thousand words, so here’s a diagram of a scenario where one logger with two handlers attached to it writes a log message with level logging.INFO:

Flow of logging objects (Image: Real Python)

Flow of logging objects (Image: Real Python)

In Python code, everything above would look like this:

import logging

import sys

logger = logging.getLogger("pylog")

logger.setLevel(logging.DEBUG)

h1 = logging.FileHandler(filename="/tmp/records.log")

h1.setLevel(logging.INFO)

h2 = logging.StreamHandler(sys.stderr)

h2.setLevel(logging.ERROR)

logger.addHandler(h1)

logger.addHandler(h2)

logger.info("testing %d.. %d.. %d..", 1, 2, 3)

There’s a more detailed map of this flow in the Logging HOWTO. What’s shown above is a simplified scenario.

Your code defines just one Logger instance, logger, along with two Handler instances, h1 and h2.

When you call logger.info("testing %d.. %d.. %d..", 1, 2, 3), the logger object serves as a filter because it also has a level associated with it. Only if the message level is severe enough will the logger do anything with the message. Because the logger has level DEBUG, and the message carries a higher INFO level, it gets the go-ahead to move on.

Internally, logger calls logger.makeRecord() to put the message string "testing %d.. %d.. %d.." and its arguments (1, 2, 3) into a bona fide class instance of a LogRecord, which is just a container for the message and its metadata.

The logger object looks around for its handlers (instances of Handler), which may be tied directly to logger itself or to its parents (a concept that we’ll touch on later). In this example, it finds two handlers:

- One with level

INFOthat dumps log data to a file at/tmp/records.log - One that writes to

sys.stderrbut only if the incoming message is at levelERRORor higher

At this point, there’s another round of tests that kicks in. Because the LogRecord and its message only carry level INFO, the record gets written to Handler 1 (green arrow), but not to Handler 2’s stderr stream (red arrow). For Handlers, writing the LogRecord to their stream is called emitting it, which is captured in their .emit().

Next, let’s further dissect everything from above.

The LogRecord Class

What is a LogRecord? When you log a message, an instance of the LogRecord class is the object you send to be logged. It’s created for you by a Logger instance and encapsulates all the pertinent info about that event. Internally, it’s little more than a wrapper around a dict that contains attributes for the record. A Logger instance sends a LogRecord instance to zero or more Handler instances.

The LogRecord contains some metadata, such as the following:

- A name

- The creation time as a Unix timestamp

- The message itself

- Information on what function made the logging call

Here’s a peek into the metadata that it carries with it, which you can introspect by stepping through a logging.error() call with the pdb module:

>>> import logging

>>> import pdb

>>> def f(x):

... logging.error("bad vibes")

... return x / 0

...

>>> pdb.run("f(1)")

After stepping through some higher-level functions, you end up at line 1517:

(Pdb) l

1514 exc_info = (type(exc_info), exc_info, exc_info.__traceback__)

1515 elif not isinstance(exc_info, tuple):

1516 exc_info = sys.exc_info()

1517 record = self.makeRecord(self.name, level, fn, lno, msg, args,

1518 exc_info, func, extra, sinfo)

1519 -> self.handle(record)

1520

1521 def handle(self, record):

1522 """

1523 Call the handlers for the specified record.

1524

(Pdb) from pprint import pprint

(Pdb) pprint(vars(record))

{'args': (),

'created': 1550671851.660067,

'exc_info': None,

'exc_text': None,

'filename': '<stdin>',

'funcName': 'f',

'levelname': 'ERROR',

'levelno': 40,

'lineno': 2,

'module': '<stdin>',

'msecs': 660.067081451416,

'msg': 'bad vibes',

'name': 'root',

'pathname': '<stdin>',

'process': 2360,

'processName': 'MainProcess',

'relativeCreated': 295145.5490589142,

'stack_info': None,

'thread': 4372293056,

'threadName': 'MainThread'}

A LogRecord, internally, contains a trove of metadata that’s used in one way or another.

You’ll rarely need to deal with a LogRecord directly, since the Logger and Handler do this for you. It’s still worthwhile to know what information is wrapped up in a LogRecord, because this is where all that useful info, like the timestamp, come from when you see record log messages.

Note: Below the LogRecord class, you’ll also find the setLogRecordFactory(), getLogRecordFactory(), and makeLogRecord() factory functions. You won’t need these unless you want to use a custom class instead of LogRecord to encapsulate log messages and their metadata.

The Logger and Handler Classes

The Logger and Handler classes are both central to how logging works, and they interact with each other frequently. A Logger, a Handler, and a LogRecord each have a .level associated with them.

The Logger takes the LogRecord and passes it off to the Handler, but only if the effective level of the LogRecord is equal to or higher than that of the Logger. The same goes for the LogRecord versus Handler test. This is called level-based filtering, which Logger and Handler implement in slightly different ways.

In other words, there is an (at least) two-step test applied before the message that you log gets to go anywhere. In order to be fully passed from a logger to handler and then logged to the end stream (which could be sys.stdout, a file, or an email via SMTP), a LogRecord must have a level at least as high as both the logger and handler.

PEP 282 describes how this works:

Each

Loggerobject keeps track of a log level (or threshold) that it is interested in, and discards log requests below that level. (Source)

So where does this level-based filtering actually occur for both Logger and Handler?

For the Logger class, it’s a reasonable first assumption that the logger would compare its .level attribute to the level of the LogRecord, and be done there. However, it’s slightly more involved than that.

Level-based filtering for loggers occurs in .isEnabledFor(), which in turn calls .getEffectiveLevel(). Always use logger.getEffectiveLevel() rather than just consulting logger.level. The reason has to do with the organization of Logger objects in a hierarchical namespace. (You’ll see more on this later.)

By default, a Logger instance has a level of 0 (NOTSET). However, loggers also have parent loggers, one of which is the root logger, which functions as the parent of all other loggers. A Logger will walk upwards in its hierarchy and get its effective level vis-à-vis its parent (which ultimately may be root if no other parents are found).

Here’s where this happens in the Logger class:

class Logger(Filterer):

# ...

def getEffectiveLevel(self):

logger = self

while logger:

if logger.level:

return logger.level

logger = logger.parent

return NOTSET

def isEnabledFor(self, level):

try:

return self._cache[level]

except KeyError:

_acquireLock()

if self.manager.disable >= level:

is_enabled = self._cache[level] = False

else:

is_enabled = self._cache[level] = level >= self.getEffectiveLevel()

_releaseLock()

return is_enabled

Correspondingly, here’s an example that calls the source code you see above:

>>> import logging

>>> logger = logging.getLogger("app")

>>> logger.level # No!

0

>>> logger.getEffectiveLevel()

30

>>> logger.parent

<RootLogger root (WARNING)>

>>> logger.parent.level

30

Here’s the takeaway: don’t rely on .level. If you haven’t explicitly set a level on your logger object, and you’re depending on .level for some reason, then your logging setup will likely behave differently than you expected it to.

What about Handler? For handlers, the level-to-level comparison is simpler, though it actually happens in .callHandlers() from the Logger class:

class Logger(Filterer):

# ...

def callHandlers(self, record):

c = self

found = 0

while c:

for hdlr in c.handlers:

found = found + 1

if record.levelno >= hdlr.level:

hdlr.handle(record)

For a given LogRecord instance (named record in the source code above), a logger checks with each of its registered handlers and does a quick check on the .level attribute of that Handler instance. If the .levelno of the LogRecord is greater than or equal to that of the handler, only then does the record get passed on. A docstring in logging refers to this as “conditionally emit[ting] the specified logging record.”

The most important attribute for a Handler subclass instance is its .stream attribute. This is the final destination where logs get written to and can be pretty much any file-like object. Here’s an example with io.StringIO, which is an in-memory stream (buffer) for text I/O.

First, set up a Logger instance with a level of DEBUG. You’ll see that, by default, it has no direct handlers:

>>> import io

>>> import logging

>>> logger = logging.getLogger("abc")

>>> logger.setLevel(logging.DEBUG)

>>> print(logger.handlers)

[]

Next, you can subclass logging.StreamHandler to make the .flush() call a no-op. We would want to flush sys.stderr or sys.stdout, but not the in-memory buffer in this case:

class IOHandler(logging.StreamHandler):

def flush(self):

pass # No-op

Now, declare the buffer object itself and tie it in as the .stream for your custom handler with a level of INFO, and then tie that handler into the logger:

>>> stream = io.StringIO()

>>> h = IOHandler(stream)

>>> h.setLevel(logging.INFO)

>>> logger.addHandler(h)

>>> logger.debug("extraneous info")

>>> logger.warning("you've been warned")

>>> logger.critical("SOS")

>>> try:

... print(stream.getvalue())

... finally:

... stream.close()

...

you've been warned

SOS

This last chunk is another illustration of level-based filtering.

Three messages with levels DEBUG, WARNING, and CRITICAL are passed through the chain. At first, it may look as if they don’t go anywhere, but two of them do. All three of them make it out of the gates from logger (which has level DEBUG).

However, only two of them get emitted by the handler because it has a higher level of INFO, which exceeds DEBUG. Finally, you get the entire contents of the buffer as a str and close the buffer to explicitly free up system resources.

The Filter and Filterer Classes

Above, we asked the question, “Where does level-based filtering happen?” In answering this question, it’s easy to get distracted by the Filter and Filterer classes. Paradoxically, level-based filtering for Logger and Handler instances occurs without the help of either of the Filter or Filterer classes.

Filter and Filterer are designed to let you add additional function-based filters on top of the level-based filtering that is done by default. I like to think of it as à la carte filtering.

Filterer is the base class for Logger and Handler because both of these classes are eligible for receiving additional custom filters that you specify. You add instances of Filter to them with logger.addFilter() or handler.addFilter(), which is what self.filters refers to in the following method:

class Filterer(object):

# ...

def filter(self, record):

rv = True

for f in self.filters:

if hasattr(f, 'filter'):

result = f.filter(record)

else:

result = f(record)

if not result:

rv = False

break

return rv

Given a record (which is a LogRecord instance), .filter() returns True or False depending on whether that record gets the okay from this class’s filters.

Here is .handle() in turn, for the Logger and Handler classes:

class Logger(Filterer):

# ...

def handle(self, record):

if (not self.disabled) and self.filter(record):

self.callHandlers(record)

# ...

class Handler(Filterer):

# ...

def handle(self, record):

rv = self.filter(record)

if rv:

self.acquire()

try:

self.emit(record)

finally:

self.release()

return rv

Neither Logger nor Handler come with any additional filters by default, but here’s a quick example of how you could add one:

>>> import logging

>>> logger = logging.getLogger("rp")

>>> logger.setLevel(logging.INFO)

>>> logger.addHandler(logging.StreamHandler())

>>> logger.filters # Initially empty

[]

>>> class ShortMsgFilter(logging.Filter):

... """Only allow records that contain long messages (> 25 chars)."""

... def filter(self, record):

... msg = record.msg

... if isinstance(msg, str):

... return len(msg) > 25

... return False

...

>>> logger.addFilter(ShortMsgFilter())

>>> logger.filters

[<__main__.ShortMsgFilter object at 0x10c28b208>]

>>> logger.info("Reeeeaaaaallllllly long message") # Length: 31

Reeeeaaaaallllllly long message

>>> logger.info("Done") # Length: <25, no output

Above, you define a class ShortMsgFilter and override its .filter(). In .addHandler(), you could also just pass a callable, such as a function or lambda or a class that defines .__call__().

The Manager Class

There’s one more behind-the-scenes actor of logging that is worth touching on: the Manager class. What matters most is not the Manager class but a single instance of it that acts as a container for the growing hierarchy of loggers that are defined across packages. You’ll see in the next section how just a single instance of this class is central to gluing the module together and allowing its parts to talk to each other.

The All-Important Root Logger

When it comes to Logger instances, one stands out. It’s called the root logger:

class RootLogger(Logger):

def __init__(self, level):

Logger.__init__(self, "root", level)

# ...

root = RootLogger(WARNING)

Logger.root = root

Logger.manager = Manager(Logger.root)

The last three lines of this code block are one of the ingenious tricks employed by the logging package. Here are a few points:

-

The root logger is just a no-frills Python object with the identifier

root. It has a level oflogging.WARNINGand a.nameof"root". As far as the classRootLoggeris concerned, this unique name is all that’s special about it. -

The

rootobject in turn becomes a class attribute for theLoggerclass. This means that all instances ofLogger, and theLoggerclass itself, all have a.rootattribute that is the root logger. This is another example of a singleton-like pattern being enforced in theloggingpackage. -

A

Managerinstance is set as the.managerclass attribute forLogger. This eventually comes into play inlogging.getLogger("name"). The.managerdoes all the facilitation of searching for existing loggers with the name"name"and creating them if they don’t exist.

The Logger Hierarchy

Everything is a child of root in the logger namespace, and I mean everything. That includes loggers that you specify yourself as well as those from third-party libraries that you import.

Remember earlier how the .getEffectiveLevel() for our logger instances was 30 (WARNING) even though we had not explicitly set it? That’s because the root logger sits at the top of the hierarchy, and its level is a fallback if any nested loggers have a null level of NOTSET:

>>> root = logging.getLogger() # Or getLogger("")

>>> root

<RootLogger root (WARNING)>

>>> root.parent is None

True

>>> root.root is root # Self-referential

True

>>> root is logging.root

True

>>> root.getEffectiveLevel()

30

The same logic applies to the search for a logger’s handlers. The search is effectively a reverse-order search up the tree of a logger’s parents.

A Multi-Handler Design

The logger hierarchy may seem neat in theory, but how beneficial is it in practice?

Let’s take a break from exploring the logging code and foray into writing our own mini-application—one that takes advantage of the logger hierarchy in a way that reduces boilerplate code and keeps things scalable if the project’s codebase grows.

Here’s the project structure:

project/

│

└── project/

├── __init__.py

├── utils.py

└── base.py

Don’t worry about the application’s main functions in utils.py and base.py. What we’re paying more attention to here is the interaction in logging objects between the modules in project/.

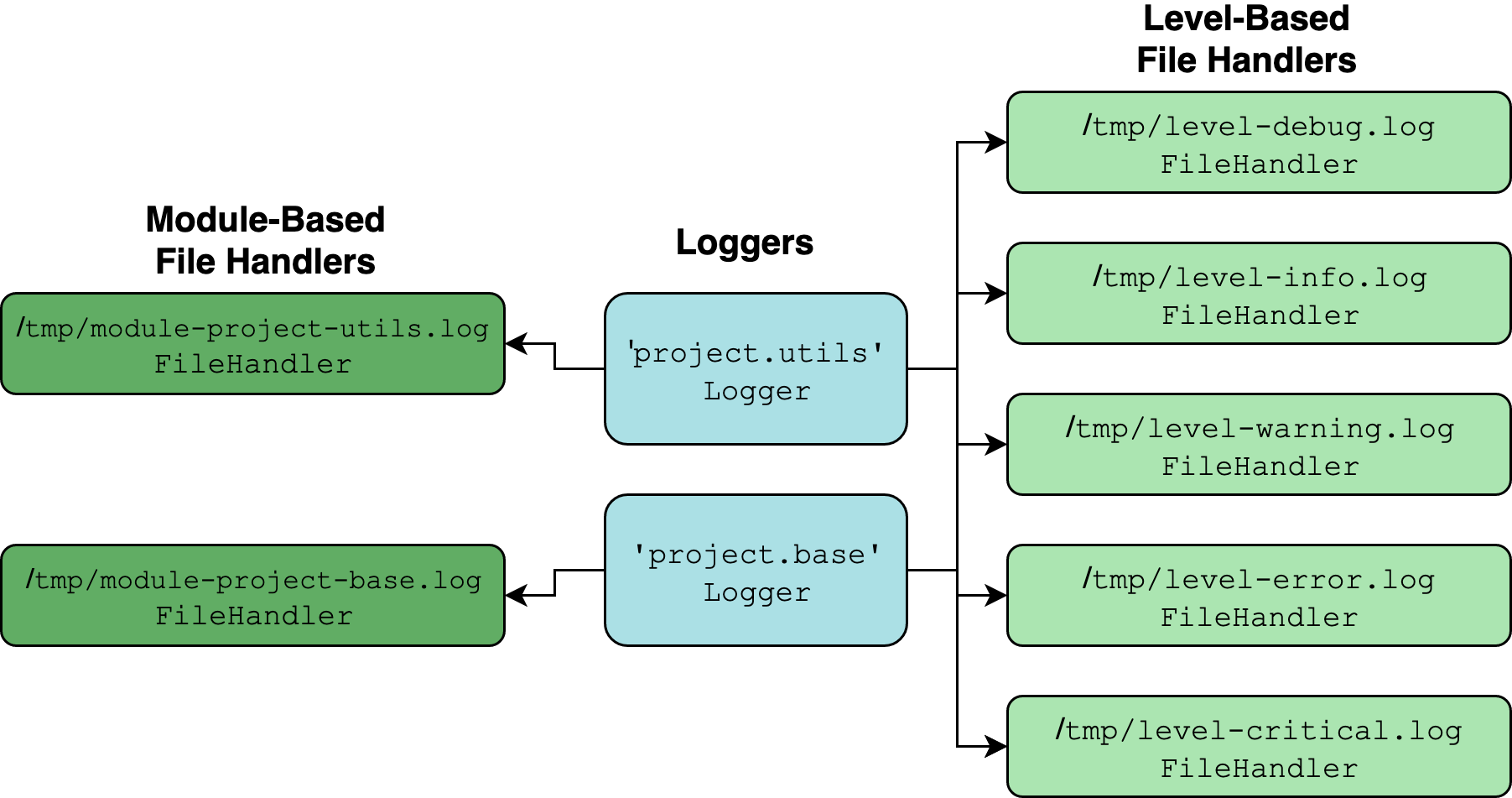

In this case, say that you want to design a multipronged logging setup:

-

Each module gets a

loggerwith multiple handlers. -

Some of the handlers are shared between different

loggerinstances in different modules. These handlers only care about level-based filtering, not the module where the log record emanated from. There is a handler forDEBUGmessages, one forINFO, one forWARNING, and so on. -

Each

loggeris also tied to one more additional handler that only receivesLogRecordinstances from that lonelogger. You can call this a module-based file handler.

Visually, what we’re shooting for would look something like this:

A multipronged logging design (Image: Real Python)

A multipronged logging design (Image: Real Python)

The two turquoise objects are instances of Logger, established with logging.getLogger(__name__) for each module in a package. Everything else is a Handler instance.

The thinking behind this design is that it’s neatly compartmentalized. You can conveniently look at messages coming from a single logger, or look at messages of a certain level and above coming from any logger or module.

The properties of the logger hierarchy make it suitable for setting up this multipronged logger-handler layout. What does that mean? Here’s a concise explanation from the Django documentation:

Why is the hierarchy important? Well, because loggers can be set to propagate their logging calls to their parents. In this way, you can define a single set of handlers at the root of a logger tree, and capture all logging calls in the subtree of loggers. A logging handler defined in the

projectnamespace will catch all logging messages issued on theproject.interestingandproject.interesting.stuffloggers. (Source)

The term propagate refers to how a logger keeps walking up its chain of parents looking for handlers. The .propagate attribute is True for a Logger instance by default:

>>> logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

>>> logger.propagate

True

In .callHandlers(), if propagate is True, each successive parent gets reassigned to the local variable c until the hierarchy is exhausted:

class Logger(Filterer):

# ...

def callHandlers(self, record):

c = self

found = 0

while c:

for hdlr in c.handlers:

found = found + 1

if record.levelno >= hdlr.level:

hdlr.handle(record)

if not c.propagate:

c = None

else:

c = c.parent

Here’s what this means: because the __name__ dunder variable within a package’s __init__.py module is just the name of the package, a logger there becomes a parent to any loggers present in other modules in the same package.

Here are the resulting .name attributes from assigning to logger with logging.getLogger(__name__):

| Module | .name Attribute |

|---|---|

project/__init__.py |

'project' |

project/utils.py |

'project.utils' |

project/base.py |

'project.base' |

Because the 'project.utils' and 'project.base' loggers are children of 'project', they will latch onto not only their own direct handlers but whatever handlers are attached to 'project'.

Let’s build out the modules. First comes __init__.py:

# __init__.py

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

logger.setLevel(logging.DEBUG)

levels = ("DEBUG", "INFO", "WARNING", "ERROR", "CRITICAL")

for level in levels:

handler = logging.FileHandler(f"/tmp/level-{level.lower()}.log")

handler.setLevel(getattr(logging, level))

logger.addHandler(handler)

def add_module_handler(logger, level=logging.DEBUG):

handler = logging.FileHandler(

f"/tmp/module-{logger.name.replace('.', '-')}.log"

)

handler.setLevel(level)

logger.addHandler(handler)

This module is imported when the project package is imported. You add a handler for each level in DEBUG through CRITICAL, then attach it to a single logger at the top of the hierarchy.

You also define a utility function that adds one more FileHandler to a logger, where the filename of the handler corresponds to the module name where the logger is defined. (This assumes the logger is defined with __name__.)

You can then add some minimal boilerplate logger setup in base.py and utils.py. Notice that you only need to add one additional handler with add_module_handler() from __init__.py. You don’t need to worry about the level-oriented handlers because they are already added to their parent logger named 'project':

# base.py

import logging

from project import add_module_handler

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

add_module_handler(logger)

def func1():

logger.debug("debug called from base.func1()")

logger.critical("critical called from base.func1()")

Here’s utils.py:

# utils.py

import logging

from project import add_module_handler

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

add_module_handler(logger)

def func2():

logger.debug("debug called from utils.func2()")

logger.critical("critical called from utils.func2()")

Let’s see how all of this works together from a fresh Python session:

>>> from pprint import pprint

>>> import project

>>> from project import base, utils

>>> project.logger

<Logger project (DEBUG)>

>>> base.logger, utils.logger

(<Logger project.base (DEBUG)>, <Logger project.utils (DEBUG)>)

>>> base.logger.handlers

[<FileHandler /tmp/module-project-base.log (DEBUG)>]

>>> pprint(base.logger.parent.handlers)

[<FileHandler /tmp/level-debug.log (DEBUG)>,

<FileHandler /tmp/level-info.log (INFO)>,

<FileHandler /tmp/level-warning.log (WARNING)>,

<FileHandler /tmp/level-error.log (ERROR)>,

<FileHandler /tmp/level-critical.log (CRITICAL)>]

>>> base.func1()

>>> utils.func2()

You’ll see in the resulting log files that our filtration system works as intended. Module-oriented handlers direct one logger to a specific file, while level-oriented handlers direct multiple loggers to a different file:

$ cat /tmp/level-debug.log

debug called from base.func1()

critical called from base.func1()

debug called from utils.func2()

critical called from utils.func2()

$ cat /tmp/level-critical.log

critical called from base.func1()

critical called from utils.func2()

$ cat /tmp/module-project-base.log

debug called from base.func1()

critical called from base.func1()

$ cat /tmp/module-project-utils.log

debug called from utils.func2()

critical called from utils.func2()

A drawback worth mentioning is that this design introduces a lot of redundancy. One LogRecord instance may go to no less than six files. That’s also a non-negligible amount of file I/O that may add up in a performance-critical application.

Now that you’ve seen a practical example, let’s switch gears and delve into a possible source of confusion in logging.

The “Why Didn’t My Log Message Go Anywhere?” Dilemma

There are two common situations with logging when it’s easy to get tripped up:

- You logged a message that seemingly went nowhere, and you’re not sure why.

- Instead of being suppressed, a log message appeared in a place that you didn’t expect it to.

Each of these has a reason or two commonly associated with it.

You logged a message that seemingly went nowhere, and you’re not sure why.

Don’t forget that the effective level of a logger for which you don’t otherwise set a custom level is WARNING, because a logger will walk up its hierarchy until it finds the root logger with its own WARNING level:

>>> import logging

>>> logger = logging.getLogger("xyz")

>>> logger.debug("mind numbing info here")

>>> logger.critical("storm is coming")

storm is coming

Because of this default, the .debug() call goes nowhere.

Instead of being suppressed, a log message appeared in a place that you didn’t expect it to.

When you defined your logger above, you didn’t add any handlers to it. So, why is it writing to the console?

The reason for this is that logging sneakily uses a handler called lastResort that writes to sys.stderr if no other handlers are found:

class _StderrHandler(StreamHandler):

# ...

@property

def stream(self):

return sys.stderr

_defaultLastResort = _StderrHandler(WARNING)

lastResort = _defaultLastResort

This kicks in when a logger goes to find its handlers:

class Logger(Filterer):

# ...

def callHandlers(self, record):

c = self

found = 0

while c:

for hdlr in c.handlers:

found = found + 1

if record.levelno >= hdlr.level:

hdlr.handle(record)

if not c.propagate:

c = None

else:

c = c.parent

if (found == 0):

if lastResort:

if record.levelno >= lastResort.level:

lastResort.handle(record)

If the logger gives up on its search for handlers (both its own direct handlers and attributes of parent loggers), then it picks up the lastResort handler and uses that.

There’s one more subtle detail worth knowing about. This section has largely talked about the instance methods (methods that a class defines) rather than the module-level functions of the logging package that carry the same name.

If you use the functions, such as logging.info() rather than logger.info(), then something slightly different happens internally. The function calls logging.basicConfig(), which adds a StreamHandler that writes to sys.stderr. In the end, the behavior is virtually the same:

>>> import logging

>>> root = logging.getLogger("")

>>> root.handlers

[]

>>> root.hasHandlers()

False

>>> logging.basicConfig()

>>> root.handlers

[<StreamHandler <stderr> (NOTSET)>]

>>> root.hasHandlers()

True

Taking Advantage of Lazy Formatting

It’s time to switch gears and take a closer look at how messages themselves are joined with their data. While it’s been supplanted by str.format() and f-strings, you’ve probably used Python’s percent-style formatting to do something like this:

>>> print("To iterate is %s, to recurse %s" % ("human", "divine"))

To iterate is human, to recurse divine

As a result, you may be tempted to do the same thing in a logging call:

>>> # Bad! Check out a more efficient alternative below.

>>> logging.warning("To iterate is %s, to recurse %s" % ("human", "divine"))

WARNING:root:To iterate is human, to recurse divine

This uses the entire format string and its arguments as the msg argument to logging.warning().

Here is the recommended alternative, straight from the logging docs:

>>> # Better: formatting doesn't occur until it really needs to.

>>> logging.warning("To iterate is %s, to recurse %s", "human", "divine")

WARNING:root:To iterate is human, to recurse divine

It looks a little weird, right? This seems to defy the conventions of how percent-style string formatting works, but it’s a more efficient function call because the format string gets formatted lazily rather than greedily. Here’s what that means.

The method signature for Logger.warning() looks like this:

def warning(self, msg, *args, **kwargs)

The same applies to the other methods, such as .debug(). When you call warning("To iterate is %s, to recurse %s", "human", "divine"), both "human" and "divine" get caught as *args and, within the scope of the method’s body, args is equal to ("human", "divine").

Contrast this to the first call above:

logging.warning("To iterate is %s, to recurse %s" % ("human", "divine"))

In this form, everything in the parentheses gets immediately merged together into "To iterate is human, to recurse divine" and passed as msg, while args is an empty tuple.

Why does this matter? Repeated logging calls can degrade runtime performance slightly, but the logging package does its very best to control that and keep it in check. By not merging the format string with its arguments right away, logging is delaying the string formatting until the LogRecord is requested by a Handler.

This happens in LogRecord.getMessage(), so only after logging deems that the LogRecord will actually be passed to a handler does it become its fully merged self.

All that is to say that the logging package makes some very fine-tuned performance optimizations in the right places. This may seem like minutia, but if you’re making the same logging.debug() call a million times inside a loop, and the args are function calls, then the lazy nature of how logging does string formatting can make a difference.

Before doing any merging of msg and args, a Logger instance will check its .isEnabledFor() to see if that merging should be done in the first place.

Functions vs Methods

Towards the bottom of logging/__init__.py sit the module-level functions that are advertised up front in the public API of logging. You already saw the Logger methods such as .debug(), .info(), and .warning(). The top-level functions are wrappers around the corresponding methods of the same name, but they have two important features:

-

They always call their corresponding method from the root logger,

root. -

Before calling the root logger methods, they call

logging.basicConfig()with no arguments ifrootdoesn’t have any handlers. As you saw earlier, it is this call that sets asys.stdouthandler for the root logger.

For illustration, here’s logging.error():

def error(msg, *args, **kwargs):

if len(root.handlers) == 0:

basicConfig()

root.error(msg, *args, **kwargs)

You’ll find the same pattern for logging.debug(), logging.info(), and the others as well. Tracing the chain of commands is interesting. Eventually, you’ll end up at the same place, which is where the internal Logger._log() is called.

The calls to debug(), info(), warning(), and the other level-based functions all route to here. _log() primarily has two purposes:

-

Call

self.makeRecord(): Make aLogRecordinstance from themsgand other arguments you pass to it. -

Call

self.handle(): This determines what actually gets done with the record. Where does it get sent? Does it make it there or get filtered out?

Here’s that entire process in one diagram:

Internals of a logging call (Image: Real Python)

Internals of a logging call (Image: Real Python)

You can also trace the call stack with pdb.

>>> import logging

>>> import pdb

>>> pdb.run('logging.warning("%s-%s", "uh", "oh")')

> <string>(1)<module>()

(Pdb) s

--Call--

> lib/python3.7/logging/__init__.py(1971)warning()

-> def warning(msg, *args, **kwargs):

(Pdb) s

> lib/python3.7/logging/__init__.py(1977)warning()

-> if len(root.handlers) == 0:

(Pdb) unt

> lib/python3.7/logging/__init__.py(1978)warning()

-> basicConfig()

(Pdb) unt

> lib/python3.7/logging/__init__.py(1979)warning()

-> root.warning(msg, *args, **kwargs)

(Pdb) s

--Call--

> lib/python3.7/logging/__init__.py(1385)warning()

-> def warning(self, msg, *args, **kwargs):

(Pdb) l

1380 logger.info("Houston, we have a %s", "interesting problem", exc_info=1)

1381 """

1382 if self.isEnabledFor(INFO):

1383 self._log(INFO, msg, args, **kwargs)

1384

1385 -> def warning(self, msg, *args, **kwargs):

1386 """

1387 Log 'msg % args' with severity 'WARNING'.

1388

1389 To pass exception information, use the keyword argument exc_info with

1390 a true value, e.g.

(Pdb) s

> lib/python3.7/logging/__init__.py(1394)warning()

-> if self.isEnabledFor(WARNING):

(Pdb) unt

> lib/python3.7/logging/__init__.py(1395)warning()

-> self._log(WARNING, msg, args, **kwargs)

(Pdb) s

--Call--

> lib/python3.7/logging/__init__.py(1496)_log()

-> def _log(self, level, msg, args, exc_info=None, extra=None, stack_info=False):

(Pdb) s

> lib/python3.7/logging/__init__.py(1501)_log()

-> sinfo = None

(Pdb) unt 1517

> lib/python3.7/logging/__init__.py(1517)_log()

-> record = self.makeRecord(self.name, level, fn, lno, msg, args,

(Pdb) s

> lib/python3.7/logging/__init__.py(1518)_log()

-> exc_info, func, extra, sinfo)

(Pdb) s

--Call--

> lib/python3.7/logging/__init__.py(1481)makeRecord()

-> def makeRecord(self, name, level, fn, lno, msg, args, exc_info,

(Pdb) p name

'root'

(Pdb) p level

30

(Pdb) p msg

'%s-%s'

(Pdb) p args

('uh', 'oh')

(Pdb) up

> lib/python3.7/logging/__init__.py(1518)_log()

-> exc_info, func, extra, sinfo)

(Pdb) unt

> lib/python3.7/logging/__init__.py(1519)_log()

-> self.handle(record)

(Pdb) n

WARNING:root:uh-oh

What Does getLogger() Really Do?

Also hiding in this section of the source code is the top-level getLogger(), which wraps Logger.manager.getLogger():

def getLogger(name=None):

if name:

return Logger.manager.getLogger(name)

else:

return root

This is the entry point for enforcing the singleton logger design:

-

If you specify a

name, then the underlying.getLogger()does adictlookup on the stringname. What this comes down to is a lookup in theloggerDictoflogging.Manager. This is a dictionary of all registered loggers, including the intermediatePlaceHolderinstances that are generated when you reference a logger far down in the hierarchy before referencing its parents. -

Otherwise,

rootis returned. There is only oneroot—the instance ofRootLoggerdiscussed above.

This feature is what lies behind a trick that can let you peek into all of the registered loggers:

>>> import logging

>>> logging.Logger.manager.loggerDict

{}

>>> from pprint import pprint

>>> import asyncio

>>> pprint(logging.Logger.manager.loggerDict)

{'asyncio': <Logger asyncio (WARNING)>,

'concurrent': <logging.PlaceHolder object at 0x10d153710>,

'concurrent.futures': <Logger concurrent.futures (WARNING)>}

Whoa, hold on a minute. What’s happening here? It looks like something changed internally to the logging package as a result of an import of another library, and that’s exactly what happened.

Firstly, recall that Logger.manager is a class attribute, where an instance of Manager is tacked onto the Logger class. The manager is designed to track and manage all of the singleton instances of Logger. These are housed in .loggerDict.

Now, when you initially import logging, this dictionary is empty. But after you import asyncio, the same dictionary gets populated with three loggers. This is an example of one module setting the attributes of another module in-place. Sure enough, inside of asyncio/log.py, you’ll find the following:

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger(__package__) # "asyncio"

The key-value pair is set in Logger.getLogger() so that the manager can oversee the entire namespace of loggers. This means that the object asyncio.log.logger gets registered in the logger dictionary that belongs to the logging package. Something similar happens in the concurrent.futures package as well, which is imported by asyncio.

You can see the power of the singleton design in an equivalence test:

>>> obj1 = logging.getLogger("asyncio")

>>> obj2 = logging.Logger.manager.loggerDict["asyncio"]

>>> obj1 is obj2

True

This comparison illustrates (glossing over a few details) what getLogger() ultimately does.

Library vs Application Logging: What Is NullHandler?

That brings us to the final hundred or so lines in the logging/__init__.py source, where NullHandler is defined. Here’s the definition in all its glory:

class NullHandler(Handler):

def handle(self, record):

pass

def emit(self, record):

pass

def createLock(self):

self.lock = None

The NullHandler is all about the distinctions between logging in a library versus an application. Let’s see what that means.

A library is an extensible, generalizable Python package that is intended for other users to install and set up. It is built by a developer with the express purpose of being distributed to users. Examples include popular open-source projects like NumPy, dateutil, and cryptography.

An application (or app, or program) is designed for a more specific purpose and a much smaller set of users (possibly just one user). It’s a program or set of programs highly tailored by the user to do a limited set of things. An example of an application is a Django app that sits behind a web page. Applications commonly use (import) libraries and the tools they contain.

When it comes to logging, there are different best practices in a library versus an app.

That’s where NullHandler fits in. It’s basically a do-nothing stub class.

If you’re writing a Python library, you really need to do this one minimalist piece of setup in your package’s __init__.py:

# Place this in your library's uppermost `__init__.py`

# Nothing else!

import logging

logging.getLogger(__name__).addHandler(NullHandler())

This serves two critical purposes.

Firstly, a library logger that is declared with logger = logging.getLogger(__name__) (without any further configuration) will log to sys.stderr by default, even if that’s not what the end user wants. This could be described as an opt-out approach, where the end user of the library has to go in and disable logging to their console if they don’t want it.

Common wisdom says to use an opt-in approach instead: don’t emit any log messages by default, and let the end users of the library determine if they want to further configure the library’s loggers and add handlers to them. Here’s that philosophy worded more bluntly by the author of the logging package, Vinay Sajip:

A third party library which uses

loggingshould not spew logging output by default which may not be wanted by a developer/user of an application which uses it. (Source)

This leaves it up to the library user, not library developer, to incrementally call methods such as logger.addHandler() or logger.setLevel().

The second reason that NullHandler exists is more archaic. In Python 2.7 and earlier, trying to log a LogRecord from a logger that has no handler set would raise a warning. Adding the no-op class NullHandler will avert this.

Here’s what specifically happens in the line logging.getLogger(__name__).addHandler(NullHandler()) from above:

-

Python gets (creates) the

Loggerinstance with the same name as your package. If you’re designing thecalculuspackage, within__init__.py, then__name__will be equal to'calculus'. -

A

NullHandlerinstance gets attached to this logger. That means that Python will not default to using thelastResorthandler.

Keep in mind that any logger created in any of the other .py modules of the package will be children of this logger in the logger hierarchy and that, because this handler also belongs to them, they won’t need to use the lastResort handler and won’t default to logging to standard error (stderr).

As a quick example, let’s say your library has the following structure:

calculus/

│

├── __init__.py

└── integration.py

In integration.py, as the library developer you are free to do the following:

# calculus/integration.py

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

def func(x):

logger.warning("Look!")

# Do stuff

return None

Now, a user comes along and installs your library from PyPI via pip install calculus. They use from calculus.integration import func in some application code. This user is free to manipulate and configure the logger object from the library like any other Python object, to their heart’s content.

What Logging Does With Exceptions

One thing that you may be wary of is the danger of exceptions that stem from your calls to logging. If you have a logging.error() call that is designed to give you some more verbose debugging information, but that call itself for some reason raises an exception, that would be the height of irony, right?

Cleverly, if the logging package encounters an exception that has to do with logging itself, then it will print the traceback, but not raise the exception itself.

Here’s an example that deals with a common typo: passing two arguments to a format string that is only expecting one argument. The important distinction is that what you see below is not an exception being raised, but rather a prettified printed traceback of the internal exception, which itself was suppressed:

>>> logging.critical("This %s has too many arguments", "msg", "other")

--- Logging error ---

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "lib/python3.7/logging/__init__.py", line 1034, in emit

msg = self.format(record)

File "lib/python3.7/logging/__init__.py", line 880, in format

return fmt.format(record)

File "lib/python3.7/logging/__init__.py", line 619, in format

record.message = record.getMessage()

File "lib/python3.7/logging/__init__.py", line 380, in getMessage

msg = msg % self.args

TypeError: not all arguments converted during string formatting

Call stack:

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

Message: 'This %s has too many arguments'

Arguments: ('msg', 'other')

This lets your program gracefully carry on with its actual program flow. The rationale is that you wouldn’t want an uncaught exception to come from a logging call itself and stop a program dead in its tracks.

Tracebacks can be messy, but this one is informative and relatively straightforward. What enables the suppression of exceptions related to logging is Handler.handleError(). When the handler calls .emit(), which is the method where it attempts to log the record, it falls back to .handleError() if something goes awry. Here’s the implementation of .emit() for the StreamHandler class:

def emit(self, record):

try:

msg = self.format(record)

stream = self.stream

stream.write(msg + self.terminator)

self.flush()

except Exception:

self.handleError(record)

Any exception related to the formatting and writing gets caught rather than being raised, and handleError gracefully writes the traceback to sys.stderr.

Logging Python Tracebacks

Speaking of exceptions and their tracebacks, what about cases where your program encounters them but should log the exception and keep chugging along in its execution?

Let’s walk through a couple of ways to do this.

Here’s a contrived example of a lottery simulator using code that isn’t Pythonic on purpose. You’re developing an online lottery game where users can wager on their lucky number:

import random

class Lottery(object):

def __init__(self, n):

self.n = n

def make_tickets(self):

for i in range(self.n):

yield i

def draw(self):

pool = self.make_tickets()

random.shuffle(pool)

return next(pool)

Behind the frontend application sits the critical code below. You want to make sure that you keep track of any errors caused by the site that may make a user lose their money. The first (suboptimal) way is to use logging.error() and log the str form of the exception instance itself:

try:

lucky_number = int(input("Enter your ticket number: "))

drawn = Lottery(n=20).draw()

if lucky_number == drawn:

print("Winner chicken dinner!")

except Exception as e:

# NOTE: See below for a better way to do this.

logging.error("Could not draw ticket: %s", e)

This will only get you the actual exception message, rather than the traceback. You check the logs on your website’s server and find this cryptic message:

ERROR:root:Could not draw ticket: object of type 'generator' has no len()

Hmm. As the application developer, you’ve got a serious problem, and a user got ripped off as a result. But maybe this exception message itself isn’t very informative. Wouldn’t it be nice to see the lineage of the traceback that led to this exception?

The proper solution is to use logging.exception(), which logs a message with level ERROR and also displays the exception traceback. Replace the two final lines above with these:

except Exception:

logging.exception("Could not draw ticket")

Now you get a better indication of what’s going on:

ERROR:root:Could not draw ticket

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 3, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 9, in draw

File "lib/python3.7/random.py", line 275, in shuffle

for i in reversed(range(1, len(x))):

TypeError: object of type 'generator' has no len()

Using exception() saves you from having to reference the exception yourself because logging pulls it in with sys.exc_info().

This makes things clearer that the problem stems from random.shuffle(), which needs to know the length of the object it is shuffling. Because our Lottery class passes a generator to shuffle(), it gets held up and raises before the pool can be shuffled, much less generate a winning ticket.

In large, full-blown applications, you’ll find logging.exception() to be even more useful when deep, multi-library tracebacks are involved, and you can’t step into them with a live debugger like pdb.

The code for logging.Logger.exception(), and hence logging.exception(), is just a single line:

def exception(self, msg, *args, exc_info=True, **kwargs):

self.error(msg, *args, exc_info=exc_info, **kwargs)

That is, logging.exception() just calls logging.error() with exc_info=True, which is otherwise False by default. If you want to log an exception traceback but at a level different than logging.ERROR, just call that function or method with exc_info=True.

Keep in mind that exception() should only be called in the context of an exception handler, inside of an except block:

for i in data:

try:

result = my_longwinded_nested_function(i)

except ValueError:

# We are in the context of exception handler now.

# If it's unclear exactly *why* we couldn't process

# `i`, then log the traceback and move on rather than

# ditching completely.

logger.exception("Could not process %s", i)

continue

Use this pattern sparingly rather than as a means to suppress any exception. It can be most helpful when you’re debugging a long function call stack where you’re otherwise seeing an ambiguous, unclear, and hard-to-track error.

Conclusion

Pat yourself on the back, because you’ve just walked through almost 2,000 lines of dense source code. You’re now better equipped to deal with the logging package!

Keep in mind that this tutorial has been far from exhaustive in covering all of the classes found in the logging package. There’s even more machinery that glues everything together. If you’d like to learn more, then you can look into the Formatter classes and the separate modules logging/config.py and logging/handlers.py.

[ Improve Your Python With 🐍 Python Tricks 💌 – Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. >> Click here to learn more and see examples ]

from Planet Python

via read more

No comments:

Post a Comment